We Spent Over $200,000 On News For YouTube And Earned Only 34 Cents In Return

At the end of last year, a video editor was given a task on his first day at our news wire agency. He was asked to select some of the best videos from a YouTube news channel we had covering China and package them together into a single compilation with some special effects.

It seemed a simple enough task to show what he could do, repackaging what we’d already done on the channel to create a Top 10 of news items.

How could it go wrong?

A screenshot from our YouTube channel

A screenshot of a video from our Chinese news wire entitled ‘Owner Struggles To Find Cute Dog Named Teddy After It Falls Asleep Among Hundreds of Teddy Bears’ that was published on YouTube.

He took his time, carefully making the selection around a common theme, then had to go to the archive for the originals of videos already on the channel and upload them again with datelines, special effects and logos. He was having to work at home because of COVID restrictions, but was nevertheless happy with his first efforts, and when completed, he uploaded it to the channel. Except he did not, because at the end, when he looked at YouTube Studio — the CMS from which YouTube accounts are managed — the item had simply vanished.

Unsure what he had done wrong, the young video editor uploaded it again, paying more attention this time, but at the end of the process, it disappeared again. Deciding that maybe the edit was corrupted, he modified it, re-saved it, and uploaded it again.

But this time, not only the video vanished, but the entire channel with it.

Unwittingly, he had fallen foul of the constantly updating YouTube algorithm that monitors and approves content and can quickly approve an item, only to decide later that it is a breach of community standards when the algorithm changes again. If it remains in the channel unchanged, YouTube may not notice, but if you upload it again, they certainly will, and it makes no difference if that video had already been there for years.

Somewhere in the 10 items that he selected, which our editorial team also believed were safe to reuse as they had already been approved and were already on that same page, was something that now breached their community guidelines. While it was previously acceptable, now it was not. The three resultant uploads, one after the other in quick succession, constituted three community strikes — and the channel was gone.

Our news content on the channel amounted to years and years of work. Our videos are uploaded with stories costing, on average, around €60 each to produce, and all of it was gone. And of course, this being YouTube, there was no chance to appeal.

It was a harsh lesson, but not the first negative one on how YouTube operates. Our experience with the channel began in 2014, in the boom years for earnings on the video service for news material, and ended last year when we stopped servicing the dozens of specialist channels we had tried — and repeatedly failed — to monetise.

In 2014, a smart lad fresh out of college and considering journalism as a career had joined our offices at the start of the year as an assistant for a complicated financial fraud story. After studying what we did in the main newsroom, he urged us to share some of our content on YouTube. When we showed interest, he created a channel and managed it for a while before deciding journalism was not for him and leaving to sell fire alarms.

A year later, I became interested in the virtually dormant YouTube project when we realised that even though we were only adding videos rarely, it was starting to bring in real money. We decided to step up the game, including YouTube uploads as one of the roles of our send desk that distributed the agency content to other media partners. After two months, the channel had earned around €6,000, with most of that in the previous two months.

However, at that point, our YouTube experiment ended abruptly when we had our first experience with how quickly YouTube channels can be snatched away by a capricious algorithm. The project had been assigned to a new video editor, who did not carefully check the community guidelines and failed to see the strikes. Three of our stories were deemed unsuitable in a single week, and the channel, and the money, were gone.

We had spent more than a year building it up. We had legitimately earned at least €6,000, although what the final amount was, YouTube would not say. All we know is that they kept the lot and refused to even reply when we asked them to return it to our team.

After that bad experience, a few of our desks dabbled in YouTube projects, but none of them really wanted to wait a year for results, and so by and large YouTube stayed out of our plans. We returned to it because of the pandemic, which rapidly accelerated the decline of our business model in terms of budgets available to buy our content and editors available to commission it.

As well as running my news agency, I also managed special projects for an association of similar news agencies around the world known as NAPA, the UK-based National Association of Press Agencies. For 20 years, I’ve been looking for the Holy Grail of how to originate content, from creation through to publication, with the bonus of getting paid so we can carry on doing more of the same.

News agencies can’t sit still, and research and development is vital for the future. We had many projects that offered the potential to replace the traditional business model. But nothing at that point on the market seemed to offer the potential of YouTube, where if you listen to popular mythology, fortunes and empires can be built in minutes. And so in 2021, seven years after YouTube first burned our fingers, we tried again. We said we’d spend a year investing in monetising channels, fully aware that we needed to be in it for the long haul. At least a year would be needed to start getting the incomes we were getting previously if all things remained equal.

We reactivated dormant YouTube channels created by desk editors as a shop window for their content, such as the one used by the Asia desk referenced at the start, and we then added new channels to the list. The first video on the Asia Desk channel after a break of two years reached 60,000 views. We were determined to do more. Carefully, we also set up a system to prefilter content to match the community guidelines, which worked until old content clashed with new guidelines.

Over a year, we spent hundreds of thousand generating content shared across a spectrum of existing and new YouTube channels. Unlike previous uploads, with the new project, we experimented with sound effects, compilations and subtitles. We had two presenters (I worked freelance doing packages for the BBC and had voice training from them, so I took one of the roles), and together we wrote scripts and presented small programmes outlining the day’s newsworthy events.

In terms of professionalism, what we did the second time round was infinitely superior to what we were doing in 2014. The first time around, we did not even have a video editor. So if there were three videos for a story, we uploaded all three with the same story separately as nobody was available to do compilations, and the investment in the channel, beyond uploading and adding the story, back then, was very little.

This time around, we did infinitely more. We would combine news items into reports, sometimes with subtitles, sometimes with special effects, and would even edit them to remove the slow bits or add pictures, graphics and narration. Some of the channels were successful, others not at all.

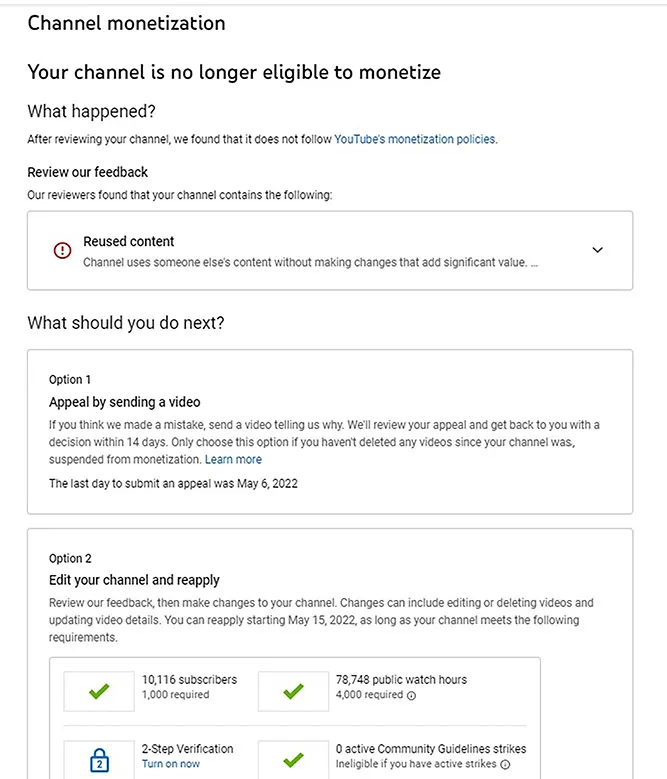

But the holy grail remained elusive even when we reached the coveted monetisation threshold — 4,000 hours of watch time and at least 1,000 subscribers. True, we managed to get one non-news channel monetised, and only one, but it was demonetised as soon as we put the news content back. Many others reached the criteria — but were never accepted to be monetised. In that brief period when the only channel that crossed the line was eligible for payments, it earned our only revenue for the whole year — a less than thrilling $0.34.

As the project progressed, more and more channels reached the same criteria needed to qualify for monetisation, and each time, they were always rejected for the same reason.

I spent a year in the studio every evening recording audio that was turned into news reports, and it wasn’t only straight news, we experimented with campaigns as well, for example. The YouTube algorithm told us that we needed to add value when using other people’s content! We were invited to create a video explaining why we felt the decision to demonetise was wrong, and we thought we had a good case. After all, unlike most, we verified the story and added the date and location on the video itself.

News at our agency follows the classic doctrine of entertainment, education and information. It is not relevant for us whether the news is left or right, tabloid or quality, or any of the other polarised positions of most media. Our priority is simple, making sure that on every story, we had gone through the complex process of trying to speak to the people involved in the news and getting confirmation to confirm it, generating several hundred words that were attached to every video.

We added not only a full story in the description but also a mixture of subtitles and narration to explain what was going on, not with automated voices, but with a real live human being either telling jokes or being suitably serious depending on the subject. We also covered the entire spectrum of news, from investigations and campaigns to cute dogs and kittens.

But it was a long way from being only fluffy kittens. One of our campaigns was about a young Turkish university student who had been raped and forced to marry her attacker after she became pregnant, and the marriage was not a happy one. She went on to endure years of abuse and violence that ended when he stripped her and beat her, threatened to kill her and their two daughters, and was accidentally shot himself when they struggled with the gun. Turkish prosecutors responded by locking her in jail and demanding 40 years behind bars.

We covered the story repeatedly, gaining international coverage, and prosecutors relented and freed her at the end of it. I have no doubt the international coverage played a part. Few, including our hard-bitten editorial team, did not shed a tear when we saw the video of her being released from the police car and embracing her girls, smelling their hair as if she could not believe what had happened. Part of the campaign had been a lengthy YouTube video urging people to sign a petition.

In a similar vein, when Turkey left the Istanbul Convention saying that women were protected anyway and arguing that the UN-brokered charter encouraged support for gay rights, we set up a webpage with an almost daily feed of stories showing that it was not doing enough, all linked to a YouTube channel to highlight each story.

YouTube took the videos down. Stories about the abuse of women, even when it is a news report highlighting a growing problem, is not something YouTube, like most social media, wanted to know about.

Fluffy kittens and stunts with ping pong balls seemed to face fewer challenges. But we do not just cover ‘negative’ news that can’t exist easily in the YouTube world, we also highlight notable technological developments or scientific discoveries.

Whenever we noticed that content was doing exceptionally well on the general channel, we split it off and created a specialist channel just for that subject, like history or green news. The €60 we spent per story was just the fee for generating the basic story. We built two small studios, one in Vienna and one in Spain, and had extra video editors specialised in matching YouTube standards. And the two presenters were doing a half-day every day at the least.

In our appeal to be monetised, we argued that this counted as adding value to our content, but again YouTube disagreed and rejected us each time. When the project ended after a year, we had created more than a dozen channels, with thousands of videos uploaded. And yet, despite millions of views and thousands of hours spent viewing our content, the total we had earned was less than a euro.

The only people who did earn were YouTube. What we noticed was that the views we got were almost always external, YouTube itself sent us almost nothing in referrals and neither did Google. Because much of our traffic was sourced from external views, they were earning revenue that they would not have received otherwise, from adverts they put in our content, but this did not help us as we were not in their partner programme.

In the eyes of YouTube, we were not entitled to payment because we were not adding value to what we created, but they it seems were. And by not putting us in the partner programme, they did not have to share it. Even worse, many of those stories had been lifted by other YouTube channels that reposted our stories — and which were monetising them. We found dozens of examples of channels copying our work, reposting our stories word for word, and earning the money that we were not.

Years ago, I wrote an editorial for the Press Gazette in which I pointed out that Google, which now owns YouTube, does not understand news, and was not competent to be deciding what people should be reading because of that.

If anything, our own YouTube experience shows that they still do not understand the value of news, or journalism. When the Columbia Journalism Review writer Mathew Ingram was reporting from the South by Southwest conference in Texas in 2020, he noted that YouTube CEO Susan Wojcicki said: “If there’s an important news event, we want to be delivering the right information,” but then quickly added that YouTube is “not a news organisation.”

He wrote: “In other words, Google wants to benefit from being a popular source for news without having to assume the responsibilities that come with being a media entity.” It is like their plan to use Wikipedia as a health warning on YouTube content promoting conspiracy theories. It underlines that Google and YouTube still don’t understand news.

If you are not in the business, you can be forgiven for thinking that you make a few phone calls, check the facts, compile it into a good narrative and job done. It is infinitely more complicated than that. In the modern world, with so much information available, 50 per cent of the work of a journalist is deciding what is a news story at all, and it is worrying that Google with all its influence over all we read is deciding that without understanding it.

My agency business is trading in news, every day we grade and categorise content and distribute it where it needs to go. We tried to do the same on YouTube, but this was “not adding value”. Small wonder that news judgement is a skill that few have nowadays, as they focus on what social media is telling them the masses are reading, and wade in to follow the crowd.

Writer Isaiah McCall described the YouTube method of managing content as a “Huxleyan dystopia of algorithm-driven content recommended by multinational corporations”. In contrast, it is against our editorial policy to include any advertising, marketing or PR in out content. Maybe that was what YouTube really meant by adding value?

We produce content that publishers are going to want to buy and we need to have a huge network to ensure there is always one publisher somewhere that will buy a given story, no matter how specialised it may be. There was another problem with YouTube, and Google, which is refusing to recognise a growing list of content and where some stories are simply not being considered.

That has implications not just for the plurality of the media, which tends to harvest anything trending that their algorithms tell them their readers will like, but it also has implications in creating the news. The news creation process is hard enough already, and newsrooms, contrary to popular belief, are not full of people who know how to make a few phone calls and string a narrative together. The best editorial teams have a production process, with spotters and commissioning editors at the beginning, sub-editors, which are the gatekeepers, at the end, and half a dozen people in between to join the two together.

And even if you have all those people, the team needs to know each other, they need to have developed systems to deal with the problems often generated by the content they create, and they are required to live and breathe an editorial workflow backed up by a code of conduct and an editorial guide. Even if you have a working newsroom, alongside all the effort and cost of creating content that adds value to YouTube, these rules that are being placed on us by social media companies are adding a further layer to make the job even harder.

Some of our biggest partners no longer buy content in certain categories because social media doesn’t want it, and if you, a member of the public, doesn’t know about it, it doesn’t exist. So whole categories of news are simply not reported on because YouTube and Google don’t want them. In the traditional media landscape, we are responsible for publication in our outlets and can decide what action to take on a reader or viewer complaint by talking to our editors. But, unfortunately, the algorithm handles the complaints on YouTube, and we are entirely at its mercy.

If YouTube decides, based on a computer-generated recommendation, that the complaint is fair, there is nothing we can do about it. And all too often, the proverbial baby is being thrown out with the bathwater. Mention anything involving windows or balconies and falling, and you will get a community strike for promoting suicide. Even if it’s someone risking their life climbing up the side of a building to rescue a young child from the balcony, it will generate a strike.

If you need any proof that the algorithm does not learn and does not seem to be applying artificial intelligence, we found one video in this category that was getting community strikes as quickly as we could appeal them. Only when we finally asked them to stop challenging the same video did the community strikes end — and it was allowed to remain.

But not only were community strikes a problem, there were also copyright strikes. News organisations are professionals in copyright, but the people we deal with are not. You can interview somebody who has copyright on a video or a picture, get a signed contract that allows you non-exclusive usage, and then fall foul of a blanket complaint when they sell it to a syndication agency days later who demand every other version be removed. Alternatively, we would find that the copyright holder who had given us permission would sometimes file a strike. Typically, they would forget but more often it would be someone else that was claiming second rights and wanted to remove all rivals. I spoke to one stressed press officer who had tried to have a video removed where it had been shared by a channel that she felt was inappropriate and did not have permission. But she accidentally arranged a strike against 500 news partners, including us, who had legitimately obtained it. Three of these strikes and the channel is gone.

In the end we spent more than $200,000 and earned $0.34.

True, this was as much an experiment as a business project, all companies need to invest in research and development if they are to grow and to stay ahead of the game, but what we have now realised is that generating €2,000 to €3,000 a month as we were in 2015 is not possible anymore. A significant factor is that YouTube does not distinguish between what we do and what an influencer does, and we simply can’t compete.

In 2015, 100,000 views on a story gave us a good income. But an influencer can put on a bikini and make a cocktail, drive a fast car and crash it, or humiliate a pal, and they will get millions of hits. Even on the most significant YouTube news channels, the news cannot compete with these numbers, which are treated the same way as we are, and they are hoovering up much of the money that I would have been earning in 2015. The sad fact is that news organisations like ours cannot compete with influencers and the mind-boggling numbers they can get for something that can be posted instantly with 10 minutes of thought, and half the time. Worse still, typically their video will include product placement that will further boost anything they get from YouTube whereas our code of conduct forbids product placement or PR.

At the time I wrote this, the Guardian reported how YouTube was named a significant conduit of online disinformation and misinformation worldwide that is “not doing enough to tackle the spread of falsehoods on its platform” by a global coalition of fact-checking organisations. A letter signed by more than 80 groups, including Full Fact in the UK and the Washington Post’s Fact Checker, says the video platform is hosting content by groups including Doctors for the Truth, which spread COVID misinformation, and videos supporting the “fraud” narrative during the US presidential election.

“YouTube is allowing its platform to be weaponised by unscrupulous actors to manipulate and exploit others and to organise and fundraise themselves. Current measures are proving insufficient,” states the letter to YouTube’s chief executive, Susan Wojcicki, which describes YouTube as a “major conduit” for falsehoods. YouTube is spending on fact-checkers, but the tragedy is that they could use that money more effectively by embracing a relationship with journalists.

Some of the best performing news stories we have done over the years were exposing fake news, because that’s what we do all the time, verify the news and when we find it’s fake, we can share that. But Google and YouTube do not support that. There is no easy way to flag it up to them except as a member of the general public, which given our experience with algorithms, hardly makes it seem worth the effort.

I found one video on YouTube in which the cute baby shark would switch halfway through to the horrific MoMo, pretty frightening if you’re a child wanting to watch something relaxing before going to bed. YouTube pays nothing for that sort of information, but we sold the story to a national newspaper in the UK and made €150, which is hundreds of times what I earned from a year of content on YouTube.

That is what journalists do, and it’s exactly what YouTube needs; journalists clued up on current affairs that are better placed to spot extremist or other dangerous content and turn it into news items than a poorly paid fact-checker.

The 2019 mosque shootings in New Zealand that left 51 dead and 40 injured were carried out by Brenton Tarrant, an extremist radicalised by YouTube videos, according to a report from the New Zealand mission of enquiry into the tragedy. The report stated: “The individual claimed that he was not a frequent commenter on extreme right-wing sites and that YouTube was, for him, a far more significant source of information and inspiration. Although he did frequent extreme right-wing discussion boards such as those on 4Chan and 8chan, the evidence we have seen is indicative of more substantial use of YouTube.” One of the songs Brenton Tarrant played while live-streaming himself as he killed was Serbia Strong, created in 1993 to celebrate the crimes of Radovan Karadzic, who is currently serving a life sentence for genocide. When it was written about by the British investigative magazine Private Eye, it was already at 1 million views. The song talks about ‘removing kebabs’, a derogatory reference to the ethnic cleansing of Muslims, and indeed Tarrant described himself as a kebab removal specialist when justifying his killing. When the attack happened, YouTube removed some of these songs, but one of the most popular, which they did not remove, had been there for seven years and reached 9 million views, according to the website ‘Know Your Meme’.

YouTube is already a key source of news for many journalists; we look at it as a way to reach people on the ground in the news we are writing about, it would be easy to report some of those fake news or improper videos to YouTube. Journalists could be paid like bounty hunters, tracking down fake news and alerting YouTube.

Indeed, our newsroom has a reporting team that speaks dozens of languages, but there will not be much fake news spotted on a budget of $0.34 that we earned from the YouTube platform. What it is doing instead of this, or offering more moderation, is organising 15-second “media literacy” events to encourage people to do more “critical thinking”.

I would argue critical journalism might be a better way for YouTube to improve what it does because, as our experience, detailed here, shows, there are many things wrong. Not many decisions seem to be being made that will make any difference. Our newsroom generates content that often ends up in the top 10 most discussed on the world’s biggest social media platforms like Facebook, and it’s not luck; it’s teamwork.

The story I reported on Medium at the start of the week is a classic example about Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old girl who died after she was held by Iran’s feared morality police. Despite it breaking at the time of Queen Elizabeth’s funeral, the story sent an echo all around the world. From small beginnings in real-life newsrooms, stories can grow to set the global agenda. We would get tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands of hits for video stories on YouTube, yet almost none of it came from YouTube referrals. It was all external sites and individuals that were valuing what we do and driving traffic to those channels. But articles like this independently analysing YouTube, which journalism should be doing, are too few and too far between.

Biting the hand that feeds you, even if it’s feeding the scraps from the table, is still not regarded as good advice for the starving, and news organisations that either count on YouTube revenue or handouts from Google may be reluctant to take on the challenge. I wrote a long email to YouTube outlining some of the concerns — I got a reply pointing out what the community guidelines were, and that was pretty much it.

At the end of the project, I still think YouTube has a lot of potential, and if it were to spend its money more wisely and work with journalists rather than undermining us, it would make a much more significant difference. The platform is excellent to work with technically, both as a contributor and consumer. Over the past year, I’ve become a fan of several news channels that I probably never would have discovered otherwise.

Another little used benefit for the news community is that YouTube demands that everybody who posts content grants other YouTube users the right to repost it if they add value, including critical analysis, as with most news reports. We used exactly this to argue against copyright strikes successfully on several occasions. MTV for example did an excellent and rather spooky video in which they used special effects to bring back to life people killed in the Beirut bombing to demand justice a year after the event. We did a story including the criticism of the project, and when MTV requested it be taken down, YouTube then put it back after accepting it was a fair comment.

That was the same reason we used to justify republishing on YouTube an expensive video of a spoiled millionaire travelling at hundreds of miles an hour down a German motorway, putting his life and others at risk even though it was technically legal. We also lifted and reposted this on our channel by reporting that German officials were looking for a loophole to prosecute him and adding criticism from the country’s Transport Minister and many others, a very different story to his “look at me and how rich and cool I am” video.

But we were experimenting and prepared to take risks; commercial editorial teams with responsibility for the integrity of a channel may not want to risk a community strike that will reduce earnings and visibility and even endanger their channel’s existence.

In my opinion, unlike many social media, YouTube is a quality product that enriches the online experience, among other things, and we could boost their readers even more. In addition, our clients increasingly want to embed our content rather than pay for it, and we could get the ad revenue rather than a fee if we were a YouTube partner.

The platform would be a great place to host and monetise if it were not for all the obstacles outlined above. But none of our clients want to have their URLs turn into dead liínks if the YouTube channels vanish. Yes, YouTube still has a lot of potential. But it should embrace journalism and not lump us in with influencers where we simply can’t compete.

But that does not mean buying us off as Google is trying to do with cash for worthy media and ignoring the rest, or telling us what we can and can’t report, or even by keeping all the revenue that pays for what we do rather than sharing it.